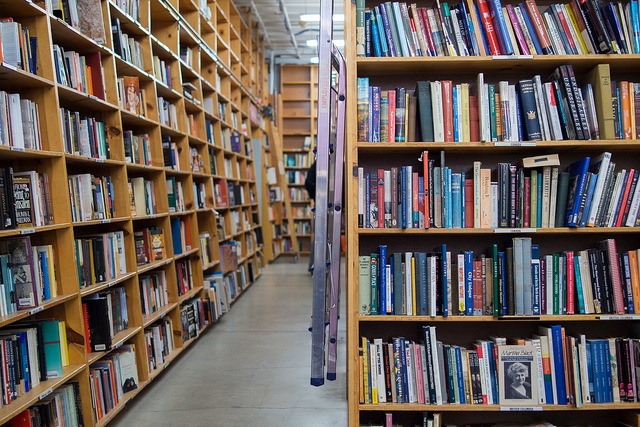

This special feature discusses the relationship between writer, agent, and editor/publisher in shaping the dynamics of the contemporary trade publishing sector

Traditionally agents have evolved to act as middlemen for authors and their editors and publishers, allowing writer’s to focus on their craft. Thompson writes that:

The writer’s world is not the same as the world of publishers, agents and booksellers… for them [writers] it is another world located somewhere else and largely mysterious in the way it works, an object of wonder, dismay or simply incomprehension depending on the writer’s experiences of it.” (2012, p. 383)

But the trade publishing sector is changing with the development of new technologies and digitisation, as well as changing economic and marketplace conditions, and many of the traditional roles are being redefined. This essay will consider the ways the changes in the trade publishing industry are shaping the dynamics of the relationships between authors, agents and editors or publishers by discussing the increasing importance of the agent, the duality between small independent and global conglomerate publishers, and the viability of self-publishing. It will discuss the current turbulence that exists between stakeholders in the sector as it adjusts to these changes, and contribute to the discourse on what the future possibilities for the relationships that exist in the trade publishing sector may be.

Literary agents first appeared in the late 1800s and effectively worked as advertising agencies for authors and their books. This was seen by many as a disruption to the relationship between authors and publishers, as it would “debase literature by emphasising the commercial aspect” (Thompson, 2012, p. 60). Having an agent meant (and still does) the author could be less involved in the business negotiations with publishers, and instead focus on writing. Initially this process worked both ways and an agent would work for authors or publishers, but they “increasingly came to see that their interests lay with their authors” (Thompson, 2012, p. 61). Agents, driven by their own self-interest in making money from commissions, capitalised on the shift they helped create in the power balance between authors and publishers. Unattached to the traditional, polite ways of the publishing sector agents by the 1980s were exploiting their newfound power to create a competitive environment of bidding wars, poaching of competitors’ authors and the splitting up of global rights amongst regions:

They displaced the centrality of the publisher by asserting control over the rights of their clients’ work and deciding which rights to allocate to which publisher and on what terms. In their eyes, the publisher was not the central player in the field but simply a means to get what they wanted to achieve on their clients’ behalf… The traditional relations of power between author and publisher were gradually overturned.” (Thompson, 2012, p. 65)

The push for high advances and increased authorial control over rights was driven by the idea that a publisher would invest more resources in a book that they have paid more for to ensure its success. All of this is done with the aim of creating a feeling of fervour for a book or author, and to secure the best deal possible. In contemporary publishing, having an agent is almost essential if an author wishes to be picked up by a major publishing house. Many major publishers now accept only solicited (agented) manuscripts, and for those times that unsolicited manuscripts are accepted they may end up buried in a ‘slush pile’ and are never seriously considered. Agents have come to hold most of the negotiating power in the sector; however this shifts again if the author has proven sales record (i.e. every book is a bestseller), and agents, editors and publishers will invest time and money in holding onto them.

As the middleman, agents must develop good working relationships with both authors, and editors and publishers. The major concerns for authors in their relationship with agents is whether or not their agent is acting within their best interests, and that they understand what the job entails:

Literary agenting always was, and still remains, an unregulated profession. Anyone can set himself up as a literary agent – all you need to do is call yourself an agent, hook up a telephone (and now an internet connection) and display some knowledge, however slight, of how the industry works.” (Thompson, 2012, p. 71)

Becoming an agent is often as simple as deciding to do so and finding some authors to represent; “only time and their bank balances accounts will tell if they are right” (Larsen, 1996, p. 30). What does this lack of regulation mean for authors? An experienced, skilled agent is able to guide authors to making the deal that will not only make them the most money, but also give them the greatest level of control and match them with an editor and publisher that will best suit their work. There is a level of learned intuition that can only come from experience, and a renegade or inexperienced agent could be the death of an author’s career.

In this sales-driven marketplace, it is vital to have someone who can sell your product effectively. Larsen (1996) outlines the following as the main issues a writer may have with their agent: contact and communication difficulties, that they are not actively pursuing sales or are unable to sell an author’s work, that they continually reject new work, or that an author has outgrown their agent and they are no longer able to provide the best platform for selling an authors work. Finding a suitable agent and cultivating this relationship takes time and effort from both author and agent, and an author’s first agent may not be their last. The best agents will have a solid client list, and well-developed connections with editors and publishers formed over time:

But at the end of the day, the standing of any agent in the field is indissolubly linked to the success or otherwise of the particular books they have sold and authors they have signed. Their client list is their CV, and their reputation as an agent, together with the trust they are able to elicit from editors and others, is shaped by the clients they represent and the rewards and awards – both financial and symbolic – that the books they sold have produced and received.” (Thompson, 2012, p. 83)

The remnants of the power shift from the 1980s and 90s and increased emphasis on profits means that authors are more likely to move between publishers and editors, and so agents have come to provide a “degree of continuity” (Clark & Phillips, 2008, p. 94). Agency skill and reputation plays a key role in an authors being published, as editors and publishing houses have come to see them as the first filter in the selection process. Editors often take more seriously manuscripts coming from particular agents that they have developed trusting relationships with, and so developing these industry connections is vital to both their authors’ and their own success. As a result, agents have taken on many of the roles once held by editors in discovering authors. Publishers may resent agents wresting power from them, but they have been quick to establish a new and useful relationship with them.

The relationship between author and editor or publisher is more tenuous than that between the author and agent. Sales figures in contemporary publishing dictate whether this relationship will be maintained or not, often regardless on the quality of the book. Despite the significance of this, it is more interesting to consider the polarisation of the field (Thompson, 2012) that has emerged in trade publishing. Large corporations were established in the publishing sector under the control of even larger, global media and communications corporations, and by the 1990s the sector was almost unrecognisable. Independent publishers had been amalgamated and umbrella organisations housed numerous imprints, “with varying degrees of autonomy depending on the strategies and policies of the corporate owners” (Thompson, 2012, p. 103). But regardless of size and ownership, publishers will always be restricted by the power of agents who influence authors on one hand, and booksellers who influence customers on the other. Booksellers are increasingly important in the digital publishing field, as Amazon holds a virtual monopoly on sales. Alongside these conglomerates, there is an emerging group of small, independent publishers whose focus is less commercial or profit driven. Epstein (2002) goes so far as to argue that in the future:

Publishing firms will be smaller, more improvisational, more likely to take risks, less costly to create and run, and more numerous than the bewildered conglomerates that now overshadow the industry and the writers and readers it serves.” (p. xi)

This is advanced thinking for the contemporary sector, but nonetheless, smaller publishers are working their way into the marketplace by catering for niche opportunities. For large publishers, the key benefit is scale and their ability to dominate a marketplace. They have the ability to consolidate central services and invest in larger amounts of infrastructure (such as warehousing, finance departments, publicity and sales) amongst their imprints can reduces costs significantly and they have reduced supplies costs as they negotiate better terms based on the large volume of business they bring and can often place increased pressure on these suppliers. Larger publishers can negotiate better terms with retailers and provide greater publicity for authors, which is especially important today as retailers a great degree of power because of their access to and influence over readers. Larger conglomerates have the ability to absorb any negative sales, which allows them to take risks in investing more in and securing authors that may or may not sell. Ultimately, these factors and the ability to offer higher advances places large publishers in a more advantageous position when negotiating with agents to secure authors. For most authors, a greater sum of money and access to more readers (sometimes on a global level) is crucial.

Small publishers have emerged in spite of large corporations dominance, sometimes because of this dominance. Epstein (2002) writes that:

Book publishing as deviated from its true nature by assuming, under duress from unfavourable market conditions and the misconceptions of remote managers, the posture of a conventional business… For owners and editors willing to work for the joy of the task, book publishing in my time has been immensely rewarding. For investors looking for conventional returns, it has been disappointing.” (p. 4)

Epstein (2002) considers that book publishing is not an industry suited to a profit driven model, and that there will be a return to more independent, editorially driven publishers that focus on quality rather than quantity. Defining a small publisher can be difficult, but they range from not-for-profits to independent presses such as Text Publishing or Scribe Publications, and those run by educational intuitions such as the University of Western Sydney’s Giramondo. Start-up costs are generally low, and are now even lower due to digital advances in trade publishing. Publishing just an eBook eliminates print costs entirely, and globalisation has meant offshore publishing is a cheap and viable option. Many small publishers outsource work such as copyediting and design to freelancers or other small companies that specialise in these tasks, and rely on an “economy of favours” (Thompson, 2012, p. 56) that takes advantages of networks and relationships that embrace freedom and creativity within the industry.

In yet another saving, some small publishers are run without dedicated office spaces, eliminating spending on real estate, as employees work from home. There are examples of small presses, particularly those publishing poetry, that operate as art organisations under a social entrepreneurship model rather than as publishers and so they may receive funding and grants from various sources, including governments and arts funds (Mannion & Espeseth, 2013). Thompson (2012) argues that “this world of small presses exists as a parallel universe to the world of the large corporate publishers” (p. 56), and so it is difficult to compare the two. What they do is different, despite operating in the same industry with the same purpose of producing books. Those working in the small publishing field are largely artistically or culturally, and editorially driven rather than profit driven and so the key difference, apart from scale, is in diversity. Small publishers operate in niche and localised markets, publishing books that would not be considered viable by large publishers:

For many small indie presses, the world of corporate publishing is seen as a sphere of commodification in which money reigns supreme and where cultural values and commitments have been sacrificed to commercial ends.” (Thompson, 2012, p. 161)

So unlike large publishers, small publishers are less caught between the power of agents and booksellers. Many readily accept unsolicited manuscripts or approach new, un-agented authors directly, which removes agents from the process. Often, established agents do not approach small publishers at all and so they focus on building relationships with smaller, new agents who will likely have new, unpublished authors looking for publishers, or they source new authors directly for themselves. For these authors, large advances are a lesser concern, with focus often being on just getting published. There are obvious disadvantageous of being a small publisher which include lack of finances, and reduced publicity and marketing opportunities.

An unusual concern is that a larger publisher may poach an author. Larger publishers look at authors who have been successful at small publishers and may poach them, offering better terms and other incentives. This includes authors they may have overlooked or rejected in that past. On some occasions, small publishers may be used as a testing ground for an author’s saleability. This affects the ability of small publishers to create a backlist and to realise the long term rewards of building an author’s career, particularly if great risk has been taken in publishing them at the beginning of their careers. Many of these vulnerabilities are negated by their ability to change quickly and independently depending on their situation, and experiment with what they publish. In reality, it is mid-size publishers rather than small publishers that are losing out in the contemporary sector and so the dynamic in the sector has become one of polarisation. Mid-size publishers outside of trade publishing, such as educational and scholarly publishers, manage well; but in trade publishing it is difficult to grow from small to mid-size, as the market does not exist. They have neither the benefits of a large conglomerate’s scale, which also often operate imprints as mid-size publishers with the backing of the overhead company, or the benefits small publisher’s niche market opportunities.

The viability of self-publishing as an option for authors, which bypasses agents, editors and publishers, is a significant impact on the dynamics in the contemporary trade publishing sector. Epstein presents the lofty idea that, in the same way many name-brand celebrity actors leave their agents and create their own production companies, name-brand writers will soon take back much of the control over their works:

Name-brand writers with the help of their agents or business managers may become their own publishers, keeping entire proceeds from the sale of their books, net of production, advertising and distribution costs.” (2002, p. 21)

While there is little evidence of this happening yet, new and unpublished authors who are not picked up by agents and publishers are exploring ways they can self-publish. Thanks to new technologies “self-publishing is experiencing a new, stigma-free reputation as a legitimate option to traditional publishing” (Herther, 2013, p. 22). The cost of producing an eBook or digital text is small, and many companies, such as Smashwords, Amazon and Apple are offering self-publishing platforms for authors at varying costs. A number of the large conglomerate publishers have recognised the impact these services may have, and have invested in these platforms; for example Penguin Random House owns Author Solutions (Herther, 2013). Authors are able to outsource editing and design to freelancers or companies in the same way small publishers do. There is also a growing field of print-on-demand options, based locally in Australia and with overseas printers, who will print and distribute copies of a text as readers request them.

Marketing and publicity are cause for concern amongst self-publishing authors, as they traditionally require large budgets, much effort and a good media contacts. This is where many self-publishing authors fail. It is increasingly important to not only get a book into the marketplace, but also have it received well. There is an assumption that self-published books are self-published because no publisher wanted them as they simply weren’t very good, however Herther (2013) argues that the concern with quality is irrelevant as bad book will “disappear into the void” (p. 25). The Internet is a partial way around this with the various social media platforms providing the ability to build an audience, as are increasingly popular online book catalogues such as GoodReads and The Reading Room which offer authors many avenues of promotion, a review system and the ability to develop connections and loyalty with readers.

Many of the digital self-publishing platforms now offer ways for authors to market and promote books. If enough ‘buzz’ can be generated in online media, it is possible that self-published works will be picked up and promoted in more mainstream media channels. Funding is an issue for self-publishers, with costs ranging from a few hundred dollars to thousands. Credit cards and bank loans are an option, as is crowd funding through sites like Pozible and Kickstarter. Many books are created this way by bloggers whose readers demand more from them, such as Anna Watson Carl of ‘The Yellow Table’ who raised over $65,000(US) on Kickstarter to publish The Yellow Table Cookbook (Carl, 2014). The consequence for the author if they choose to self-publish is that it reduces the time they can dedicate to writing. However, if they can dedicate the time and effort to self-publishing and make a success of it, they retain total control over their work and what they do with this success. It is still to early to determine how much of an impact self-publishing will have on the trade publishing sector, but it is certain that it opens up an option outside of traditional publishers.

The contemporary trade publishing sector is facing great changes and future uncertainty as technology and marketplace demands change the way authors approach having their books published. The changing relationships between authors, agents and publishers or editors are changing the dynamics of the whole industry. Authors now have more control than ever before through their agents increased power over publishers in negotiations and the availability of viable self-publishing options such as digital book platforms and print-on-demand services. Changes by publishers to the way they structure their businesses, and the polarisation between large, conglomerate publishers and small, independent publishers further shifts this dynamic. Contemporary trade publishing is a vastly different field to when it first began, and its future remains largely uncertain as the changes discussed in the essay continue to force authors, agents and publishers to adjust the way they produce books and redefine the roles they play and relationships they cultivate.

Click here to leave a comment and let us know what you think of this article!

References:

Benedetti, C. (2005). The Empty Cage: Inquiry into the Mysterious Disappearance of the Author. New York, USA: Cornell University Press

Bramble, J. Training Needs for the Book Publishing & Printing Industries. In Cope. B & Freeman, R. (2002). Developing Knowledge Workers in the Printing & Publishing Industries. Altona, Aust.: Common Ground Publishing (RMIT University)

Cain, A. (2013, March 26). A how-to guide for self-publishing. Sydney Morning Herald

Carl, A.W. (2014). The Yellow Table Cookbook

Clark, G. & Phillips, A. (2008). Inside Book Publishing. Oxford, UK: Routledge

Cloonan, W. & Postel, J-P. (1997). Literary Agents & the Novel in 1996. The French Review, 40(6), p. 796-806.

Coronel, T. What Next for the Australian Book Trade? In Stinson, E. (Ed.). (2013). By The Book? Contemporary Publishing in Australia. Clayton, Aust.: Monash University Publishing.

Darnton, R. (2009). The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future. New York, USA: PublicAffairs.

Davis, M. Publishing in the End Times. In Stinson, E. (Ed.). (2013). By the Book? Contemporary Publishing in Australia. Clayton, Aust.: Monash University Publishing.

Entrepreneur Magazine (2012). Self Publishing: Entrepreneur Magazine’s Step-By-Step Startup Guide. California, USA: Entrepreneur Media.

Epstein, J. (2002). Book Business: Publishing Past, Present, & Future. New York, USA: W.W. Norton.

Herther, N.K. (2013). Today’s Self-Publishing Gold Rush Complicates Distribution Channels. Online Searcher, 37(5), p. 22-26.

Larsen, M. (1996). Literary Agents: What They Do, How they do it, & How to find & Work With the Right One for You. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Lupton, E. (Ed.). (2008). Indie Publishing: How to Design & Produce Your Own Book. New York, USA: Princeton Architectural Press.

Mannion, A. & Espeseth, A. Small Press Social Entrepreneurship. In Stinson, E. (Ed.). (2013). By the Book? Contemporary Publishing in Australia. Clayton, Aust.: Monash University Publishing.

Thompson, J.B. (2012). Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the 21st Century. New York, USA: Plume.

Unseld, S. (1980). The Author & His Publisher. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

West, J.L.W. (1988). American Authors & the Literary Marketplace since 1900. Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Young, S. (2007). The Book is Dead (Long Live the Book). Sydney, Aust.: UNSW Press Ltd.

Ziguras, C., Reinke, L. & Scanlon, C. Trends in Education for the Book Industry: Australian & International Experiences. In Cope. B & Freeman, R. (2002).

Developing Knowledge Workers in the Printing & Publishing Industries. Altona, Aust.: Common Ground Publishing (RMIT University).